U.S. interest in deep sea mining presents opportunities for developing countries

By Jesse Schatz, Director, Qorvis

In July 2024, member nations of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) gathered in Kingston, Jamaica. Among other milestones, the body elected a new president and continued debate to set rules and regulations related to the emerging deep sea mining industry. Established in 1982 by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the body manages the commercialization of resources located on the seafloor of international waters. As the seafloor holds trillions of dollars in critical minerals (including cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, and copper), the role of the ISA as the arbiter of these resources has increasingly gained the attention of international stakeholders.

This has included the United States, which, according to the Wall Street Journal, will fund Department of Defense-related research into the feasibility of harvesting seafloor critical minerals. However, despite many U.S. leaders’ identification of seafloor minerals as a possible means to diversify supply chains from China, the U.S.’ lack of accession to UNCLOS prevents the U.S. from full ISA membership, and subsequently any ability to directly influence regulations or engage in direct exploitation of open-ocean mineral resources.

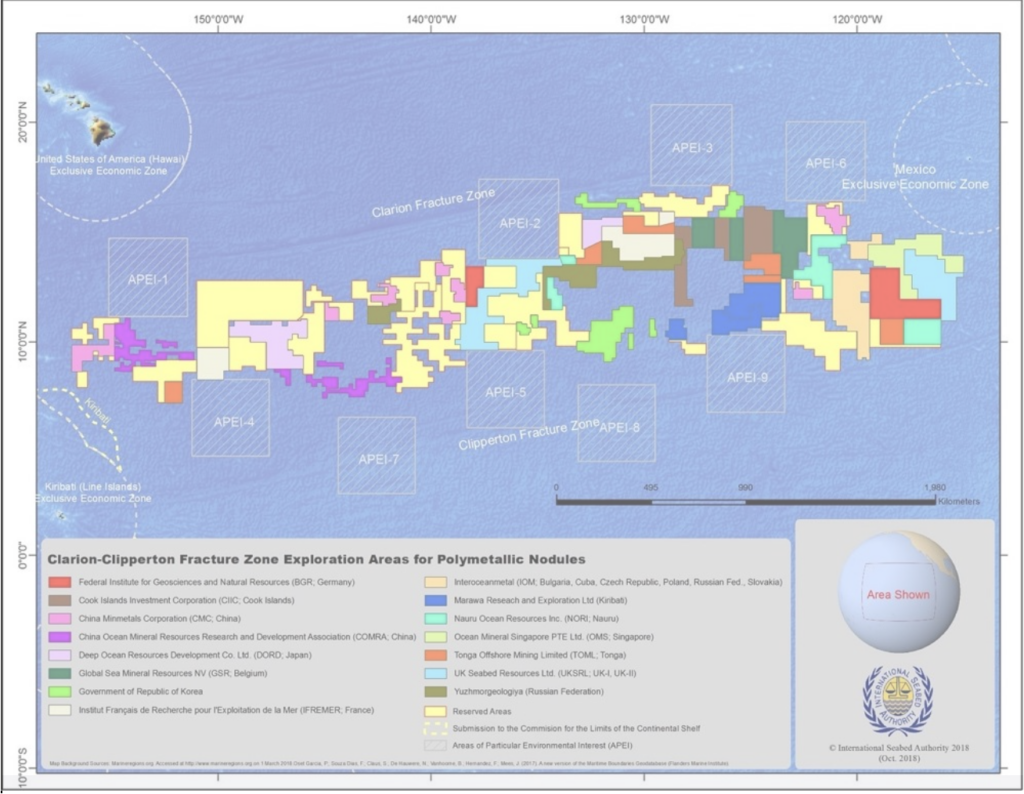

While all countries are free to engage in mining in their own maritime territory, non-ISA members are unable to do so in international waters. This includes the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a large expanse in the Pacific known to be full of metal-rich polymetallic nodules and where most serious efforts at pursuing deep sea mining have taken place. Contracts to explore and potentially exploit seafloor resources in international waters are exclusively extended by the ISA, and only to its member countries or private-sector actors sponsored by member countries. To date, exploration areas have been extended to global heavyweights like China, Germany, Japan, UK, and South Korea, but also to small island nations like Nauru, Kiribati, Tonga, and the Cook Islands. Importantly for this latter group, UNCLOS requires that seafloor resources aid the economic situation of developing countries. While details are not yet final, this could include fees paid to developing countries or the distribution of some profits.

While the U.S. is unlikely to ratify UNCLOS in the near future, Washington, D.C. and other UNCLOS holdouts still have a range of tools at their disposal to exert influence over this emerging industry. For the U.S, this includes brokering bilateral critical minerals agreements with ISA allies, incorporating small island developing states into existing U.S.-led multinational critical minerals initiatives, and planning for U.S.-led economic corridors to address the logistic challenges presented by deep sea mining.

Bilateral Agreements

In recent years, the U.S. has forged several bilateral agreements specific to critical minerals cooperation including 2023 agreements with Australia and Japan; the latter includes provisions to facilitate trade, bolster supply chains, and implement labor rights standards, and is reportedly a model for U.S.-UK and U.S.-EU critical minerals agreements in process. As the U.S. seeks to increase its geopolitical influence in the Pacific, there is no reason why similar agreements could not also be reached with Pacific Island partner nations, gaining new access to metals while extending U.S. investment and expertise.

Multinational Groupings

Similarly, the U.S. has spearheaded recent multinational initiatives pertaining to critical minerals, namely the Minerals Security Partnership. The MSP has identified the diversification of and investment in supply chains, promotion of high ESG standards, and recycling as key priorities. Deep sea mining could contribute to satisfying each of these components, and the U.S. could potentially extend its influence into the sector by encouraging membership of interested Pacific Island nations within MSP.

Trade and Logistics

Finally, with most early exploration activities happening in some of the most remote expanses of the Pacific, physically transporting polymetallic nodules—from the seafloor to the surface, onward to onshore refining facilities, and eventually to various manufacturing hubs—presents challenges related to trade and logistics. These needs could be factored into U.S.-led trade initiatives such as the emerging India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). This could be particularly advantageous in light of July 2024 reports that New Delhi will seek exploration licenses from the ISA in the CCZ. The various manufacturing, shipping logistics, and refining requirements play to the strengths of IMEC’s respective European, Arabian, and South Asian partners, and all its members could stand to benefit from an integration of the deep sea mining supply chain.

What’s Next

The emerging deep sea mining industry unites U.S. interests with those of its global partners. If small island states can strategize to overcome their lack of representation in Washington, D.C., and create closer connections with U.S. decision makers, then they will be aptly positioned to emerge as partners of choice for the U.S. as it seeks to influence this industry.

Jesse Schatz is a Director at Qorvis in Washington, D.C. He specializes in strategic communications and intelligence-gathering for a diverse portfolio of accounts spanning Washington, D.C., Riyadh, and Dubai.